Processes Management

- A process is simply an instance of one or more related tasks (threads) executing on your computer. It is not the same as a program or a command.

- The largest PID has been limited to a

16-bitnumber, or32768. - It is possible to alter this value by changing

/proc/sys/kernel/pid_max, since it may be inadequate for larger servers. - As processes are created, eventually they will reach pid_max, at which point they will start again at

PID = 300. - A single command may actually start several processes simultaneously.

- Some processes are independent of each other and others are related. A failure of one process may or may not affect the others running on the system.

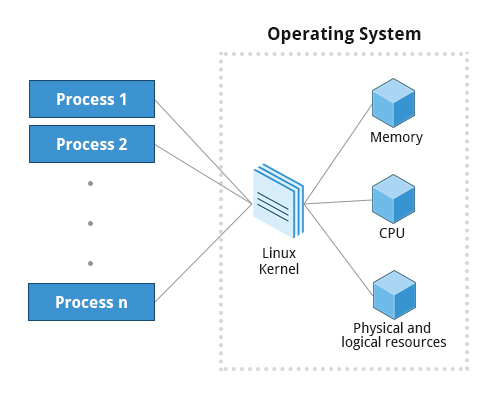

- Processes use many system resources, such as memory, CPU (central processing unit) cycles, and peripheral devices, such as network cards, hard drives, printers and displays.

- The operating system (especially the kernel) is responsible for allocating a proper share of these resources to each process and ensuring overall optimized system utilization.

- Every process has a pid (Process ID), a ppid (Parent Process ID), and a pgid (Process Group ID). In addition, every process has program code, data, variables, file descriptors, and an environment.

- Processes are controlled by scheduling, which is completely preemptive. Only the kernel has the right to preempt a process; they cannot do it to each other.

- Every process is executing some program. At any given moment, the process may take a snapshot of itself by trapping the state of its CPU registers, where it is executing in the program, what is in the process’ memory, and other information. This is the context of the process.

- Since processes can be scheduled in and out when sharing CPU time with others (or have to be put to sleep while waiting for some condition to be fulfilled, such as the user to make a request or data to arrive), being able to store the entire context when swapping out the process and being able to restore it upon execution resumption is critical to the kernel’s ability to do context switching.

- Every process has permissions based on which user has called it to execute. It may also have permissions based on who owns its program file. Programs which are marked with an ”s” execute bit have a different ”effective” user id than their ”real” user id. These programs are referred to as setuid programs. They run with the user-id of the user who owns the program, where a non-setuid program runs with the permissions of the user who starts it. setuid programs owned by root can be a security problem.

- The passwd command is an example of a setuid program. It is runnable by any user. When a user executes this program, the process runs with root permission in order to be able to update the write-restricted files, /etc/passwd and /etc/shadow, where the user passwords are maintained.

- When a process is started, it is isolated in its own user space to protect it from other processes. This promotes security and creates greater stability.

- Processes do not have direct access to hardware. Hardware is managed by the kernel, so a process must use system calls to indirectly access hardware. System calls are the fundamental interface between an application and the kernel.

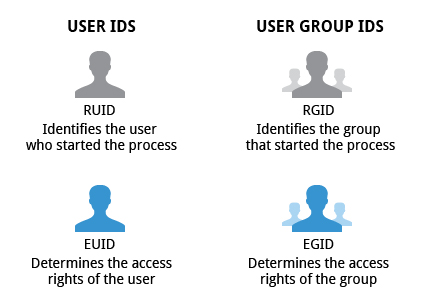

User and Group IDs

- Many users can access a system simultaneously, and each user can run multiple processes. The operating system identifies the user who starts the process by the Real User ID (RUID) assigned to the user.

- The user who determines the access rights for the users is identified by the Effective UID (EUID). The EUID may or may not be the same as the RUID.

- Users can be categorized into various groups. Each group is identified by the Real Group ID (RGID). The access rights of the group are determined by the Effective Group ID (EGID). Each user can be a member of one or more groups.

Controlling Processes

-

ulimitis a built-in bash command that displays or resets process resource limits. -

A system administrator may need to change some of these values in either direction:

- To restrict capabilities so an individual user and/or process cannot exhaust system resources, such as memory, cpu time or the maximum number of processes on the system.

- To expand capabilities so a process does not run into resource limits; for example, a server handling many clients may find that the default of 1024 open files makes its work impossible to perform.

Set Limits

-

You can set any particular limit by running the following command:

ulimit [options] [limit] #increase the maximum number of file descriptors to 1600 ulimit -n 1600 -

Note that the changes only affect the current shell. To make changes that are effective for all logged-in users, you need to modify

/etc/security/limits.confand then reboot.ulimit -a real-time non-blocking time (microseconds, -R) unlimited core file size (blocks, -c) unlimited data seg size (kbytes, -d) unlimited scheduling priority (-e) 0 file size (blocks, -f) unlimited pending signals (-i) 30530 max locked memory (kbytes, -l) 8192 max memory size (kbytes, -m) unlimited open files (-n) 1024 pipe size (512 bytes, -p) 8 POSIX message queues (bytes, -q) 819200 real-time priority (-r) 0 stack size (kbytes, -s) 8192 cpu time (seconds, -t) unlimited max user processes (-u) 30530 virtual memory (kbytes, -v) unlimited file locks (-x) unlimited

Hard and Soft Limits

There are two kinds of limits:

-

Hard: The maximum value, set only by the root user, that a user can raise the resource limit to.Command:

ulimit -H -n Output:4096 -

Soft: The current limiting value, which a user can modify, but cannot exceed the hard limit.Command:

ulimit -S -n Output:1024

Process Operations

Process Types

- A terminal window (one kind of command shell) is a process that runs as long as needed. It allows users to execute programs and access resources in an interactive environment. Programs also run in the background, which means they become detached from the shell.

- Processes can be of different types according to the task being performed.

| Process Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Interactive Processes | Need to be started by a user, either at a command line or through a graphical interface such as an icon or a menu selection. | bash, firefox, top |

| Batch Processes | Automatic processes which are scheduled from and then disconnected from the terminal. These tasks are queued and work on a FIFO (First-In, First-Out) basis. | updatedb, ldconfig |

| Daemons | Server processes that run continuously. Many are launched during system startup and then wait for a user or system request indicating that their service is required. | httpd, sshd, libvirtd |

| Threads | Lightweight processes. These are tasks that run under the umbrella of a main process, sharing memory and other resources, but are scheduled and run by the system on an individual basis. An individual thread can end without terminating the whole process and a process can create new threads at any time. Many non-trivial programs are multi-threaded. | firefox, gnome-terminal-server |

| Kernel Threads | Kernel tasks that users neither start nor terminate and have little control over. These may perform actions like moving a thread from one CPU to another, or making sure input/output operations to disk are completed. | kthreadd, migration, ksoftirqd |

A daemon process is a background process whose sole purpose is to provide some specific service to users of the system. Here are some more information about daemons:

- They can be quite efficient because they only operate when needed

- Many daemons are started at boot time

- Daemon names often (but not always) end with d, e.g. httpd and systemd-udevd

- Daemons may respond to external events (systemd-udevd) or elapsed time (crond)

- Daemons generally have no controlling terminal and no standard input/output devices

- Daemons sometimes provide better security control

- Some examples include xinetd, httpd, lpd, and vsftpd

Process State

- Running : A process in the Running state is either currently receiving attention from the CPU (in other words, executing) or waiting in a queue ready to run. A queued process will be selected to run when its priority has elevated it to first in the queue and the operating system has an idle CPU.

- Close Waiting (Sleeping) : A process in the Waiting (or Sleeping) state is waiting on a request that it has made (usually I/O) and cannot proceed further until the request is completed. When the request is completed, an event interrupts the O/S to allow a CPU to be reassigned to the waiting process and it will continue processing.

- Close Stopped : A process may be Stopped, meaning execution of instructions has been suspended. This state is commonly experienced when a programmer wants to examine the executing programs memory, CPU registers, flags or other attributes. Once this is done, the process may be resumed.

- Close Zombie : A Zombie state is entered when a process terminates. Zombie processes are important, because each Zombie continues to take up space in the O/S’s process table. The process table has an entry for each active process in the system. A Zombie process has all of its resources released except its process table entry.

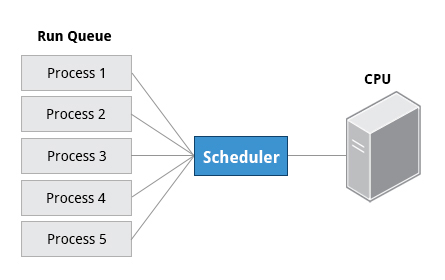

Process Scheduling and States

- A critical kernel function called the scheduler constantly shifts processes on and off the CPU, sharing time according to relative priority, how much time is needed and how much has already been granted to a task.

- When a process is in a so-called running state, it means it is either currently executing instructions on a CPU, or is waiting to be granted a share of time (a time slice) so it can execute. All processes in this state reside on what is called a run queue and on a computer with multiple CPUs, or cores, there is a run queue on each.

- Sometimes processes go into what is called a sleep state, generally when they are waiting for something to happen before they can resume, perhaps for the user to type something. In this condition, a process is said to be sitting on a wait queue.

- There are some other less frequent process states, especially when a process is terminating. Sometimes, a child process completes, but its parent process has not asked about its state. Amusingly, such a process is said to be in a zombie state; it is not really alive, but still shows up in the system’s list of processes.

Process and Thread IDs

- At any given time, there are always multiple processes being executed. The operating system keeps track of them by assigning each a unique process ID (PID) number. The PID is used to track process state, CPU usage, memory use, precisely where resources are located in memory, and other characteristics.

- New PIDs are usually assigned in ascending order as processes are born. Thus, PID 1 denotes the init process (initialization process), and succeeding processes are gradually assigned higher numbers.

ID Type Description Process ID (PID) Unique Process ID number Parent Process ID (PPID) Process (Parent) that started this process. If the parent dies, the PPID will refer to an adoptive parent; on recent kernels, this is kthreadd which has PPID=2. Thread ID (TID) Thread ID number. This is the same as the PID for single-threaded processes. For a multi-threaded process, each thread shares the same PID, but has a unique TID.

Terminating a Process

-

At some point, one of applications may stop working properly. How do you eliminate it?

-

To terminate a process, you can type

kill -SIGKILL <pid> kill -9 <pid> -

Note, however, you can only kill your own processes; those belonging to another user are off limits, unless you are root.

Creating Processes

- Forking: In a Linux system, new processes are constantly created. This process creation is commonly referred to as forking, where the original parent process continues running, and a new child process is started.

- Fork and Exec: The fork operation is often followed by an exec operation, where the parent process terminates, and the child process inherits the parent’s process ID (PID). The combination of fork and exec is commonly referred to as “fork and exec.”

- In older UNIX systems, a similar concept called “spawn” was used, but it differs in certain details and is not a standard part of Linux.

- The

sshddaemon is an example of a process created by the init process. The init process executes the sshd init script, which is responsible for launching the sshd daemon. Each remote user connecting via SSH gets their own copy of the sshd daemon to handle their login requests.

- The

- Internal kernel processes perform maintenance tasks, such as flushing buffers to disk, load balancing across CPUs, handling queued work for device drivers, etc. These processes run continuously, sleeping when there is no work to be done.

- The first user process in Linux is called

initand has aprocess ID (PID) of 1. Subsequent processes are forked from init or other running processes. - When a parent process dies, its child processes are adopted by the init process.

- Kernel-created processes can be identified by their names surrounded by square brackets [..] in the output from the ps command.

Creating processes in Shell

When a user executes a command in a command shell interpreter, such as bash, the following takes place:

-

A new process is created (forked from the user’s login shell)

-

A wait system call puts the parent shell process to sleep

-

The command is loaded onto the child process’s space via the exec system call, replacing bash

-

The command completes executing, and the child process dies via the exit system call

-

The parent shell is re-awakened by the death of the child process and proceeds to issue a new shell prompt

-

The parent shell then waits for the next command request from the user, at which time the cycle will be repeated.

-

If a command is issued for background processing (by adding an ampersand -&- at the end of the command line), the parent shell skips the wait request and is free to issue a new shell prompt immediately, allowing the background process to execute in parallel. Otherwise, for foreground requests, the shell waits until the child process has completed or is stopped via a signal.

-

Some shell commands (such as echo and kill) are built into the shell itself, and do not involve loading of program files. For these commands, neither a fork nor an exec is issued for the execution.

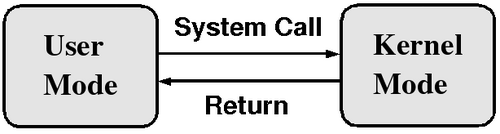

Two Execution Modes

- Processes or individual threads within a process can execute in either user mode or system mode (kernel mode) in the context of kernel development.

- The execution mode determines the instructions that can be executed and is enforced at the hardware level rather than software.

- The mode is not a system state but rather a processor state. In a multi-core or multi-CPU system, each unit can have its own individual execution mode.

- Intel CPUs refer to user mode as Ring 3 and system mode as Ring 0.

- User Mode:

- Processes execute in user mode, except when performing system calls.

- When a process starts, it is isolated in its own user space to provide security and stability. This is known as process resource isolation.

- Each process in user mode has its own memory space, with certain parts possibly shared with other processes. However, a user process cannot directly read from or write to the memory space of other processes.

- Even if a process is run by the root user or is a

setuidprogram, it operates in user mode with limited access to hardware. It can only access hardware through system calls. - When an application needs to perform a privileged operation, it makes a system call, which switches the execution mode from user mode to kernel mode. After the system call is completed, the process returns to user mode.

- Processes execute in user mode, except when performing system calls.

- System (Kernel) Mode:

- In kernel mode, the CPU has full access to all hardware resources, including peripherals, memory, and disks.

- Applications need to issue system calls to access these resources. A system call triggers a context switch from user mode to kernel mode.

- Application code never runs in kernel mode itself; only the system call, which is kernel code, executes in kernel mode.

- After the system call is completed, a return value is produced, and the process switches back to user mode.

- Kernel mode is also used for handling hardware interrupts, running scheduling routines, and performing other management tasks in the system, unrelated to user processes.

Process Priorities

- At any given time, many processes are running (i.e. in the run queue) on the system. However, a CPU can actually accommodate only one task at a time. Some processes are more important than others, so Linux allows you to set and manipulate process priority. Higher priority processes grep preferential access to the CPU.

- Real-time priority can also be assigned to time-sensitive tasks, such as controlling machines through a computer or collecting incoming data. This is just a very high priority and is not to be confused with what is called hard real-time which is conceptually different, and has more to do with making sure a job gets completed within a very well-defined time window.

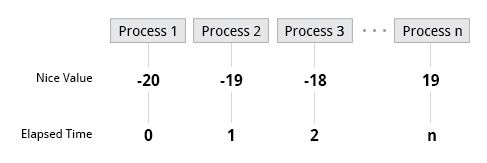

- The priority for a process can be set by specifying a nice value, or niceness, for the process. The lower the nice value, the higher the priority.

Modifying the Nice Value

-

reniceis used to raise or lower the nice value of an already running process. It basically lets you change the nice value on the fly.#Raise the nice value of pid 20003 to 5 with this command: renice +5 -p 20003 #To change the niceness of an already running process, it is easy to use the renice command, as in renice +3 13848 #which will reset the niceness to 3 for the process with pid = 13848. -

By default, only a superuser can decrease the niceness; i.e., increase the priority. However, it is possible to give normal users the ability to decrease their niceness within a predetermined range, by editing the following file:

/etc/security/limits.conf. -

After a non-privileged user has increased the nice value, only a superuser can lower it back.

-

In Linux, a nice value of

-20represents the highest priority and19represents the lowest.

-

Low values are assigned to important processes, while high values are assigned to processes that can wait longer.

-

A process with a high nice value simply allows other processes to be executed first.

#runs myprog with a nice value of 10. nice -n 10 myprog #runs myprog with the lowest priority, a nice value of 19 nice -n 19 myprog #runs myprog with the highest priority, a nice value of -20. nice -n -20 myprog

Process Metrics and Process Control

Load Averages

- The load average is the average of the load number for a given period of time. It takes into account processes that are:

- Actively running on a CPU.

- Considered runnable, but waiting for a CPU to become available.

- Sleeping: i.e. waiting for some kind of resource (typically, I/O) to become available.

- The load average can be viewed by running

w,toporuptime.

Interpreting Load Averages

uptime

19:26:28 up 2 days, 12:08, 2 users, load average: 0.45, 0.17, 0.12The load average is displayed using three numbers (0.45, 0.17, and 0.12). Assuming system is a single-CPU system, the three load average numbers are interpreted as follows:

-

0.45: For the last minute the system has been 45% utilized on average.

-

0.17: For the last 5 minutes utilization has been 17%.

-

0.12: For the last 15 minutes utilization has been 12%.

-

If we saw a value of 1.00 in the second position, that would imply that the single-CPU system was 100% utilized, on average, over the past 5 minutes; this is good if we want to fully use a system.

-

A value over 1.00 for a single-CPU system implies that the system was over-utilized: there were more processes needing CPU than CPU was available.

-

If we had more than one CPU, say a quad-CPU system, we would divide the load average numbers by the number of CPUs.

- In this case, for example, seeing a 1 minute load average of 4.00 implies that the system as a whole was 100% (4.00/4) utilized during the last minute.

-

Short-term increases are usually not a problem. A high peak you see is likely a burst of activity, not a new level.

- For example, at start up, many processes start and then activity settles down. If a high peak is seen in the 5 and 15 minute load averages, it may be cause for concern.

Background and Foreground Processes

- Foreground jobs run directly from the shell, and when one foreground job is running, other jobs need to wait for shell access (at least in that terminal window if using the GUI) until it is completed. This is fine when jobs complete quickly. But this can have an adverse effect if the current job is going to take a long time (even several hours) to complete.

- In such cases, run the job in the background and free the shell for other tasks. The background job will be executed at lower priority, which, in turn, will allow smooth execution of the interactive tasks, and other commands can be types in the terminal window while the background job is running.

- By default, all jobs are executed in the foreground.

- You can put a job in the background by suffixing

&to the command, for example:updatedb &. - Either use

CTRL-Zto suspend a foreground job orCTRL-Cto terminate a foreground job and can always use thebgandfgcommands to run a process in the background and foreground, respectively.

Managing Jobs

- The jobs utility displays all jobs running in background. The display shows the job ID, state, and command name.

jobs -lprovides the same information asjobs, and adds the PID of the background jobs.- The background jobs are connected to the terminal window, so, if you log off, the jobs utility will not show the ones started from that window.

Listing and Monitoring Processes

- The

/procfilesystem can also be helpful in monitoring processes, as well as other items, on the system. - The

/procfilesystem is an interface to the kernel data structures. /proccontains a subdirectory for each active process, named by the process id (PID)./proc/selfis the currently executing process. Some tunable parameters are in the/procdirectories.TOOL PURPOSE topProcess activity, dynamically updated uptimeHow long the system is running and the average load psDetailed information about processes pstreeA tree of processes and their connections mpstatMultiple processor usage iostatCPU utilization and I/O statistics sarDisplay and collect information about system activity numastatInformation about NUMA (Non-Uniform Memory Architecture) straceInformation about all system calls a process makes

The ps Command (System V Style)

psprovides information about currently running processes keyed by PID. For repetitive update of this status, usetopor other commonly installed variants (such ashtoporatop) from the command line, or invoke distribution’s graphical system monitor application.pshas many options for specifying exactly which tasks to examine, what information to display about them, and precisely what output format should be used.psdisplay all processes running under the current shell ps -udisplay information of processes for a specified username ps -efdisplays all the processes in the system in full detail ps -eLfdisplays one line of information for every thread ps auxps -C "bash"Only shows information about specific command. Ex- “bash”

The ps Command (BSD Style)

pshas another style of option specification, which stems from the BSD variety of UNIX, where options are specified without preceding dashes.- For example, the command

ps auxdisplays all processes of all users. - The command

ps axoallows you to specify which attributes you want to view.

The Process Tree

pstreedisplays the processes running on the system in the form of a tree diagram showing the relationship between a process and its parent process and any other processes that it created.- Repeated entries of a process are not displayed, and threads are displayed in curly braces.

The top command

- While a static view of what the system is doing is useful, monitoring the system performance live over time is also valuable.

- One option would be to run

**ps**at regular intervals, say, every few seconds. A better alternative is to use**top**to get constant real-time updates (every two seconds by default), until you exit by typing**q.top**clearly highlights which processes are consuming the most CPU cycles and memory (using appropriate commands from within**top**).

First Line of the top Output

-

The first line of the

topoutput displays a quick summary of what is happening in the system, including:- How long the system has been up

- How many users are logged on

- What is the load average

-

The load average determines how busy the system is.

- A load average of 1.00 per CPU indicates a fully subscribed, but not overloaded, system.

- If the load average goes above this value, it indicates that processes are competing for CPU time.

- If the load average is very high, it might indicate that the system is having a problem, such as a runaway process (a process in a non-responding state).

Second Line of the top Output

- The second line of the

topoutput displays the total number of processes, the number of running, sleeping, stopped, and zombie processes. - Comparing the number of running processes with the load average helps determine if the system has reached its capacity or perhaps a particular user is running too many processes.

- The stopped processes should be examined to see if everything is running correctly

Third Line of the top Output

- The third line of the

topoutput indicates how the CPU time is being divided between the users (us) and the kernel (sy) by displaying the percentage of CPU time used for each. - The percentage of user jobs running at a lower priority (

niceness - ni) is then listed. - Idle mode (

id) should be low if the load average is high, and vice versa. - The percentage of jobs waiting (

wa) for I/O is listed. - Interrupts include the percentage of hardware (

hi) vs. software interrupts (si). Steal time (st) is generally used with virtual machines, which has some of its idle CPU time taken for other uses.

Fourth and Fifth Lines of the top Output

- The fourth and fifth lines of the

topoutput indicate memory usage, which is divided in two categories:- Physical memory (RAM) – displayed on line 4.

- Swap space – displayed on line 5.

- Both categories display total memory, used memory, and free space.

- Once the physical memory is exhausted, the system starts using swap space (temporary storage space on the hard drive) as an extended memory pool, and since accessing disk is much slower than accessing memory, this will negatively affect system performance.

- If the system starts using swap often, you can add more swap space. However, adding more physical memory should also be considered.

Process List of the top Output

- Each line in the process list of the

topoutput displays information about a process. By default, processes are ordered by highest CPU usage. The following information about each process is displayed:- Process Identification Number (PID)

- Process owner (USER)

- Priority (PR) and nice values (NI)

- Virtual (VIRT), physical (RES), and shared memory (SHR)

- Status (S)

- Percentage of CPU (%CPU) and memory (%MEM) used

- Execution time (TIME+)

- Command (COMMAND).

Interactive Keys with top

topcan be utilized interactively for monitoring and controlling processes. While top is running in a terminal window, single-letter commands can be used to change its behavior.Command Output tDisplay or hide summary information (rows 2 and 3) mDisplay or hide memory information (rows 4 and 5) ASort the process list by top resource consumers rRenice (change the priority of) a specific processes kKill a specific process fEnter the top configuration screen oInteractively select a new sort order in the process list