System, NTP and Package Management

-

The Network Time Protocol (NTP) is the most popular and reliable protocol for setting the local time by consulting established Internet servers.

-

Linux distributions always come with a working NTP setup, which refers to specific time servers run or relied on by the distribution. This means that no setup, beyond “on” or “off”, is generally required for network time synchronization.

-

Ascertain your current resolution by typing at the command line:

xdpyinfo | grep dimNetwork Manager

- Network Manager was developed to make things easier and more uniform across distributions. It can list all available networks (both wired and wireless), allow the choice of a wired, wireless, or mobile broadband network, handle passwords, and set up Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). Except for unusual situations, it is generally best to let Network Manager establish your connections and keep track of your settings.

- Wired connections usually do not require complicated or manual configuration. The hardware interface and signal presence are automatically detected, and then Network Manager sets the actual network settings via Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP).

- For static configurations that do not use DHCP, manual setup can also be done easily through Network Manager. You can also change the Ethernet Media Access Control (MAC) address if your hardware supports it. The MAC address is a unique hexadecimal number of your network card.

- Network Manager can also manage your VPN connections.

- It supports many VPN technologies, such as native IPSec, Cisco OpenConnect (via either the Cisco client or a native open source client), Microsoft PPTP, and OpenVPN.

Package Managers: Installing and Updating Software

Each package in a Linux distribution provides one piece of the system, such as the Linux kernel, the C compiler, utilities for manipulating text or configuring the network, or for your favorite web browsers and email clients.

- Each package contains the files and other instructions needed to make one software component work well and cooperate with the other components that comprise the entire system.

- Packages can depend on each other. For example, a package for a web-based application written in PHP can depend on the PHP package.

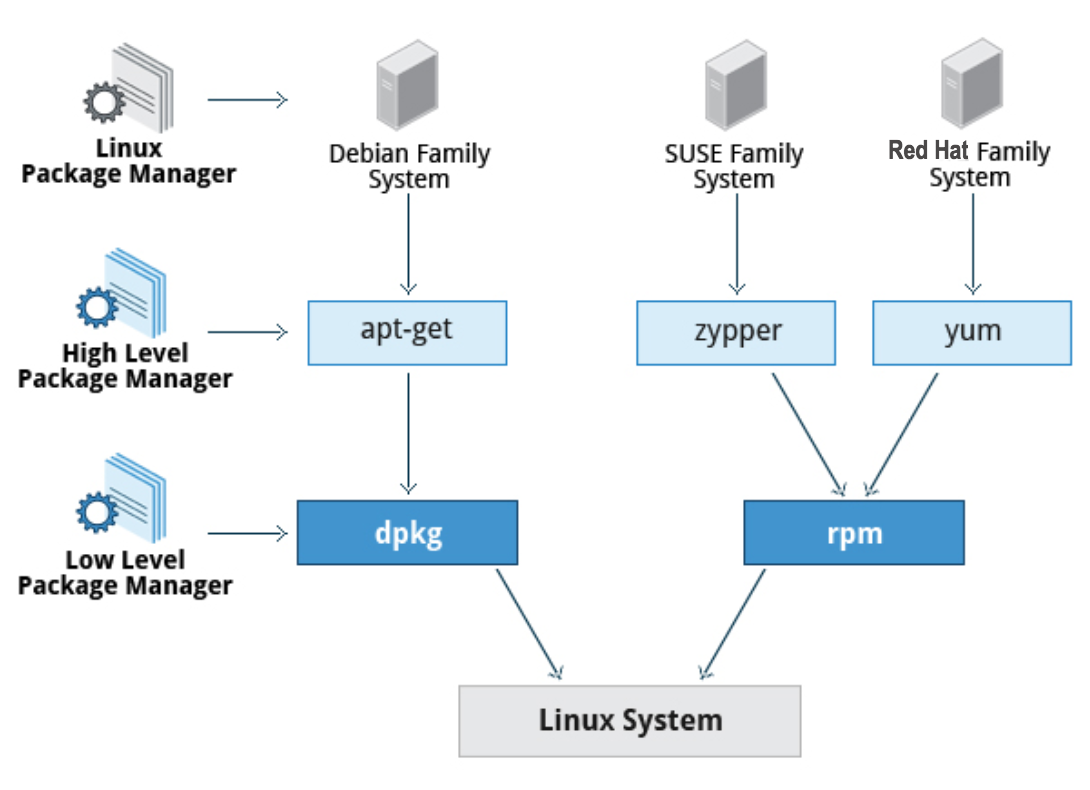

- There are two broad families of package managers: those based on Debian and those which use RPM as their low-level package manager. The two systems are incompatible, but broadly speaking, provide the same features and satisfy the same needs.

Why use Packages?

- Automation: No need for manual installs and upgrades

- Scalability: Install packages on one system, or 10,000 systems

- Repeatability and predictability

- Security and auditing

Software Packaging Concepts

A given package may contain executable files, data files, documentation, installation scripts and configuration files. Also included are metadata attributes such as version numbers, checksums, vendor information, dependencies, descriptions, etc.

Package management systems supply the tools that allow system administrators to automate installing, upgrading, configuring and removing software packages in a known, predictable and consistent manner. These systems:

- Gather and compress associated software files into a single package (archive), which may require other packages to be installed first

- Allow for easy software installation or removal

- Can verify file integrity via an internal database

- Can authenticate the origin of packages

- Facilitate upgrades

- Group packages by logical features

- Manage dependencies between packages

Upon installation, all that information is stored locally into an internal database, which can be conveniently queried for version status and update information.

Package Types

Binary Packages : Binary packages contain files ready for deployment, including executable files and libraries. These are architecture-dependent.

- Binary packages are the ones that system administrators have to deal with most of the time.

- On

64-bitsystems that can run 32-bit programs, you may have two binary packages installed for a given program, perhaps one withx86_64oramd64in its name, and the other withi386ori686in its name.

Source Packages : Source packages are used to generate binary packages; one should always be able to rebuild a binary package from the source package. One source package can be used for multiple architectures.

- Source packages can be helpful in keeping track of changes and source code used to come up with binary packages. They are usually not installed on a system by default, but can always be retrieved from the vendor.

- It should always be possible to rebuild binary packages from their source packages; for example on RPM-based systems one can rebuild the p7zip binary package by running the following command:

rpmbuild --rebuild -rb p7zip-16.02-16.el8.src.rpm

#place the results in /root/rpmbuild (below is the command, followed by the output):

root/rpmbuild>find . -name "*rpm"

./RPMS/x86_64/p7zip-plugins-16.02-16.el8.x86_64.rpm

./RPMS/x86_64/p7zip-debugsource-16.02-16.el8.x86_64.rpm

./RPMS/x86_64/p7zip-plugins-debuginfo-16.02-16.el8.x86_64.rpm

./RPMS/x86_64/p7zip-16.02-16.el8.x86_64.rpm

./RPMS/noarch/p7zip-doc-16.02-16.el8.noarch.rpmArchitecture-Independent Packages : Architecture-independent packages contain files and scripts that run under script interpreters, as well as documentation and configuration files.

Meta-Packages : Meta-packages are groups of associated packages that collect everything needed to install a relatively large subsystem, such as a desktop environment, or an office suite, etc.

Package Management Systems Available:

All systems have a lower-level utility which handles the details of unpacking a package and putting the pieces in the right places. Most of the time, you will be working with a higher-level utility which knows how to download packages from the Internet and can manage dependencies and groups for you.

Packaging Tool Levels :

- Low Level Utilities :

- This simply installs or removes a single package, or a list of packages, each one of which is individually and specifically named. Dependencies are not fully handled, only warned about or produce an error:

- If another package needs to be installed first, installation will fail.

- If the package is needed by another package, removal will fail.

- The

rpmanddpkgutilities play this role for the packaging systems that use them.

- This simply installs or removes a single package, or a list of packages, each one of which is individually and specifically named. Dependencies are not fully handled, only warned about or produce an error:

- High Level Utilities

- This solves the dependency problems:

- If another package or group of packages needs to be installed before software can be installed, such needs will be satisfied.

- If removing a package interferes with another installed package, the administrator will be given the choice of either aborting, or removing all affected software.

- The

dnfandzypperutilities (and the older yum) take care of the dependency resolution for rpm systems, andaptandapt-cacheand other utilities take care of it fordpkgsystems.

- This solves the dependency problems:

Package Sources

- Every Linux distribution has one or more package repositories for obtaining software and updates. External repositories can also be added, such as the EPEL set of version-dependent repositories which work well with RHEL since their source is Fedora and the maintainers are close to Red Hat.

Creating Software Packages

- Building your own custom software packages makes it easy to distribute and install your own software. Almost every version of Linux has some mechanism for doing this.

- Building your own package allows you to control exactly what goes in the software and exactly how it is installed. You can create the package so that installing it runs scripts that perform all tasks needed to install the new software and/or remove the old software, such as:

- Creating needed symbolic links

- Creating directories as needed

- Setting permissions

- Anything that can be scripted

There are many formats available:

- RPM for Red Hat and SUSE-based systems

- DEB for Debian for Debian-based systems

- TGZ for Slackware

- APK for Android

- Debian package file names are based on fields that represent specific information. The standard naming format for a binary package is:

<name>_<version>-<revision_number>_<architecture>.deb

# as in:

logrotate_3.14.0-4_amd64.debFor historical reasons, the 64-bit x86 platform is called amd64 rather than x86_64, and distributors such as Ubuntu manage to insert their name in the package name.

- A source package consists of at least three files:

- An upstream tarball, ending with

.tar.gz - A description file, ending with

.dsc - A second tarball that contains any patches to the upstream source, and additional files created for the package, and ends with

.debian.tar.gzor.diff.gz, depending on distribution.

- An upstream tarball, ending with

Debian Packaging

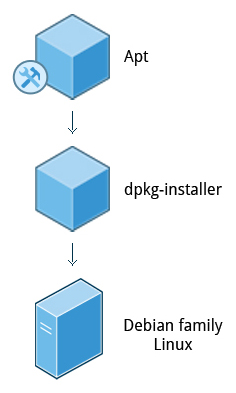

- dpkg is the underlying package manager for these systems. It can install, remove, and build packages. Unlike higher-level package management systems, it does not automatically download and install packages and satisfy their dependencies.

- Package files have a

.debsuffix and the DPKG database resides in the/var/lib/dpkgdirectory. - For Debian-based systems, the higher-level package management system is the Advanced Package Tool (APT) system of utilities.

- Generally, while each distribution within the Debian family uses APT, it creates its own user interface on top of it (for example, apt and apt-get, synaptic, gnome-software, Ubuntu Software Center, etc).

- Although apt repositories are generally compatible with each other, the software they contain generally is not. Therefore, most repositories target a particular distribution (like Ubuntu), and often software distributors ship with multiple repositories to support multiple distributions.

DPKG Queries

# To see what version of a particular package is installed

dpkg -s dpkg | grep -i version

Version: 1.19.7ubuntu3.2

# Verify all packages on the system

dpkg -V

??5?????? c /etc/logrotate.conf

??5?????? c /etc/logrotate.d/apt

??5?????? c /etc/logrotate.d/bootlog

....

# List all packages installed:

dpkg -l

# List files installed in the wget package:

dpkg -L wget

# Show information about an installed package:

dpkg -s wget

# Show information about a package file:

dpkg -I webfs_1.21+ds1-8_amd64.deb

# List files in a package file:

dpkg -c webfs_1.21+ds1-8_amd64.deb

# Show what package owns the /etc/init/networking.conf file:

dpkg -S /etc/init/networking.conf

# Verify the installed package's integrity:

dpkg -V package

# Install or upgrade the a package (ex. foobar)

sudo dpkg -i foobar.deb

# To remove all of an installed package except for its configuration files

sudo dpkg -r package

# To remove all of an installed package, including its configuration files (-P stands for purge)

sudo dpkg -P packageAPT : What Is APT?

For use on Debian-based systems, the APT (Advanced Packaging Tool) set of programs provides a higher level of intelligent services for using the underlying dpkg program, and plays the same role as dnf on Red Hat-based systems. The main utilities are apt and apt-cache. It can automatically resolve dependencies when installing, updating and removing packages. It accesses external software repositories, synchronizing with them and retrieving and installing software as needed.

The APT system works with Debian packages whose files have a .deb extension.

Once again, we are going to ignore graphical interfaces (on your computer), such as Synaptic or the Ubuntu Software Center, or other older front ends to APT, such as aptitude.

apt vs. apt-get

- For almost all interactive purposes, it is no longer necessary to use apt-get; one can just use the shorter name apt. However, you will see apt-get used all the time out of habit, and it works better in scripts.

#Install new packages or update a package which is already installed:

sudo apt install [package]

#Remove a package from the system. This does not remove the configuration files:

sudo apt remove [package]

#Remove a package and its configuration files from a system:

sudo apt --purge remove [package]

#Synchronize the package index files with their sources. The indexes of available packages are fetched from the location(s) specified in /etc/apt/sources.list:

sudo apt update

#Upgrade is used to apply all available updates to packages already installed; dist-upgrade will not update to a whole new distribution version as is commonly misunderstood:

sudo apt upgrade

sudo apt dist-upgrade#Install apt-file first, and update its database, as in:

sudo apt-get install apt-file

sudo apt-file update

#To search the repository for a package named apache2:

apt-cache search apache2

#To display basic information about the apache2 package:

apt-cache show apache2

#To display detailed information about the apache2 package:

apt-cache showpkg apache2

#List all dependent packages for apache2:

apt-cache depends apache2

#Search the repository for a file named apache2.conf:

apt-file search apache2.conf

#List all files in the apache2 package:

apt-file list apache2

#Get rid of any packages not needed anymore, such as older Linux kernel versions:

sudo apt autoremove

#Cleans out cache files and any archived package files that have been installed:

sudo apt cleanRed Hat Package Manager (RPM)

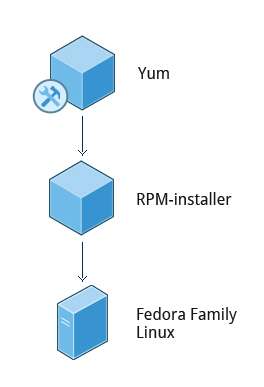

- Red Hat Package Manager (RPM) is the other package management system popular on Linux distributions. It was developed by Red Hat, and adopted by a number of other distributions, including SUSE/openSUSE, Mageia, CentOS, Oracle Linux, and others.

- The higher-level package manager differs between distributions. Red Hat family distributions historically use RHEL/CentOS and Fedora uses dnf, while retaining good backwards compatibility with the older yum program.

Package File Names:

-

Binary RPM Package: The naming format for a binary RPM package consists of the following fields:

<name>: The name of the package.<version>: The version of the package.<release>: The release number of the package.<distro>: The distribution or repository from which the package originates.<architecture>: The architecture for which the package is built.

Example:sed-4.5-2.e18.x86_64.rpm

-

Source RPM Package: The naming format for a source RPM package follows a similar structure as the binary package:

<name>: The name of the package.<version>: The version of the package.<release>: The release number of the package.<distro>: The distribution or repository from which the package originates..src.rpm: Denotes that it is a source package.

Example:sed-4.5-2.e18.src.rpm

RPM Database and Helper Programs

-

RPM Database Location: The default system directory for RPM database files is

/var/lib/rpm. The RPM database files are stored in the form of Berkeley DB hash files. It is important not to manually modify these database files, and any updates or modifications should be performed using therpmprogram. -

Specifying Database Directory: The

-dbpathoption can be used with therpmprogram to specify an alternative database directory. This can be useful, for example, when examining an RPM database copied from another system. -

Rebuilding Database: The

-rebuilddboption is used to rebuild the database indices from the installed package headers. This option is typically used for repairing the database, rather than starting from scratch. Example command:sudo rpm --rebuilddb. -

Helper Programs and Scripts: RPM provides various helper programs and scripts that are located in the

/usr/lib/rpmdirectory. These utilities support different functionalities related to RPM package management. -

Number of Helper Programs: To check the number of helper programs available on a system, you can use the command

ls /usr/lib/rpm | wc -l. The output will display the count of lines, which corresponds to the number of helper programs installed. -

RPM Configuration Files: RPM looks for default settings in the following order:

/usr/lib/rpm/rpmrc/etc/rpmrc~/.rpmrc

All of these configuration files are read, and RPM does not stop as soon as it finds one that exists. To specify an alternative rpmrc file, the

--rcfileoption can be used.

Queries

All rpm inquiries include the -q option, which can be combined with numerous other query options:

-f: allows you to determine which package a file came from-l: lists the contents of a specific package-a: all the packages installed on the system-i: information about the package-p: run the query against a package file instead of the package database

| TASK | COMMAND |

|---|---|

| Which version of a package is installed? | rpm -q bash |

| Which package did this file come from? | rpm -qf /bin/bash |

| What files were installed by this package? | rpm -ql bash |

| Show information about this package. | rpm -qi bash |

| Show information about this package from the package file, not the package database. | rpm -qip foo-1.0.0-1.noarch.rpm |

| List all installed packages on this system. | **rpm -qa** |

A couple of other useful parameters are --requires and --whatprovides.

The --requires option will return a list of prerequisites for a package, while

the --whatprovides option will show what installed package provides a particular requisite package. Below are a few sample commands:

rpm -q --requires bash

rpm -qp --requires foo-1.0.0-1.noarch.rpm

rpm -q --whatprovides libc.so.6Verifying Packages

The -V option to rpm allows you to verify whether the files from a particular package are consistent with the system’s RPM database. Use the

rpm -Va command to verify all packages on the system.

S: filesize differsM: mode differs (permissions and file type)5: MD5 sum differsD: device major/minor number mismatchL: readLink path mismatchU: user ownership differsG: group ownership differsT: mTime differs

In the output (you only see output if there is a problem each of the characters denotes the result of a comparison of attribute(s) of the file to the value of those attribute(s) recorded in the database.

A single ”.” (period) means the test passed, while a single ”?” (question mark) indicates the test could not be performed (e.g. file permissions prevent reading). Otherwise, the character denotes the failure of the corresponding --verify test.

No output when everything is OK.

rpm -V bash

None.

\#Output indicating that a file’s size, checksum, and modification time have changed.

rpm -V logrotate

S.5....T. c /etc/logrotate.conf

\#Output indicating that a file is missing.

sudo mv /sbin/logrotate /sbin/logrotate_KEEP

rpm -V logrotate

S.5....T. c /etc/logrotate.conf

missing /usr/sbin/logrotateInstalling Packages

RPM performs a number of tasks when installing a package:

- Dependency checks

- Conflict checks

- Commands required before installation

- Handles configuration files with intelligent care

- Unpacks files from package and installs them with correct attributes

- Commands required after installation

- Updates system RPM database

Dependency checks are necessary because some packages will not operate properly unless some other package is also installed.

Conflicts include attempts to install an already-installed package, or to install an older version over a newer version.

The person who builds a package can specify that certain tasks be performed before or after the install.

To install a package, the rpm -i command is used, as in:

sudo rpm -ivh bash-4.4.19-12.el8_0.x86_64where the -i is for install, -v is for verbose, and -h means print hash marks to show progress.

When installing a configuration file, if the file exists and has been changed since the previous version of the package was installed, RPM saves the old version with the suffix .rpmsave. This allows you to integrate the changes you have made to the old configuration file into the new version of the file. This feature depends on properly created RPM packages.

In addition to installing files in the right place, RPM also sets attributes such as permissions, ownership, and modification (build) time.

Every time RPM installs a package, it updates information in the system database. It uses this information when checking for conflicts.

Uninstalling Packages:

-

Package Uninstallation: The

-eoption is used with therpmcommand to uninstall (erase) a package. If the package is not installed, the command will produce an error message. A successful uninstallation does not generate any output.Example:

sudo rpm -e system-config-lvm Output: package system-config-lvm is not installed -

Error Due to Dependencies: Uninstalling a package may fail if it is required by other packages on the system. In such cases, the

rpmcommand will display error messages listing the dependencies preventing the uninstallation.Example:

sudo rpm --test -e xz Output: error: Failed dependencies: xz is needed by (installed) pcp-5.1.1-4.el8_3.x86_64 xz is needed by (installed) sos-3.9.1-6.el8.noarch xz is needed by (installed) gettext-devel-0.19.8.1-17.el8.x86_64 ... -

Testing Uninstallation: The

-testoption can be used witheto check whether the uninstallation would succeed or fail without actually performing the uninstallation. If the operation would be successful, no output is displayed. Adding thevvoption provides more detailed information. -

Important Note: It is crucial not to remove (erase/uninstall) the

rpmpackage itself. Doing so can lead to system instability. In such cases, the only solution is to reinstall the operating system or boot into a rescue environment. -

Package Name vs. RPM File Name: When uninstalling a package, the package name should be used as the argument, not the RPM file name.

-

Dependencies may vary: Dependency lists may differ depending on the specific Linux distribution being used.

Updating Packages:

-

Package Update: The

-Uvhoption is used with therpmcommand to update a package. The original package, if already installed, is replaced by the newer version specified.Example:

rpm -Uvh bash-4.4.19-12.el8.x86_64.rpm -

Updating Multiple Packages: It is possible to provide a list of package names instead of just one when updating packages.

-

Upgrade Process: During an upgrade, the already installed package is removed after the newer version is installed. However, configuration files from the original installation are preserved with a

.rpmsaveextension. -

Handling Package Installations: If the

Uoption is used, and the package is not already installed, it will be installed without any error. This option allows installing a package if it is not present or upgrading it if it is already installed. -

Limitations of

-iOption: The-ioption is not intended for upgrades. If you attempt to install a new RPM package over an older one using this option, it will fail with error messages as it tries to overwrite existing system files. -

Installing Different Versions: Different versions of the same package can be installed if they do not contain the same files. This scenario is commonly seen with kernel packages and library packages from alternative architectures.

-

Downgrading with

-U: If you want to downgrade a package using the-Uoption, i.e., replacing the current version with an earlier version, you must include the-oldpackageoption in the command line.

Freshening Packages:

- Package Freshening: The

rpmcommand with the-Fvhoption can be used to freshen packages. By runningsudo rpm -Fvh *.rpm, it attempts to freshen all the packages in the current directory. - Freshening Process:

- If an older version of a package is currently installed on the system, it will be upgraded to the newer version found in the directory.

- If the version of the package on the system is the same as the one in the directory, no action is taken.

- If there is no version of a package currently installed on the system, the package in the directory is ignored.

- Upgrading vs. Freshening: Both upgrading and freshening will install a new package if the original package is already loaded. However, freshening is specifically useful when you have downloaded several new patches and want to upgrade the packages that are already installed, without installing any new packages.

- Applying Multiple Patches: Freshening can be advantageous when you need to apply multiple patches or upgraded packages simultaneously. It allows for convenient and efficient updating of packages in bulk.

Note: The *.rpm wildcard used in the example assumes that all the relevant RPM packages are present in the current directory.

Upgrading the Linux Kernel:

-

Kernel Upgrade and Reboot: Installing a new kernel on a system requires a reboot to take effect. It is important to note that performing an upgrade (

-U) of the kernel will remove the currently running old kernel. This means that if any issues occur after the reboot, reverting back to the old kernel will not be possible since it has been removed. -

Installing New Kernel: To install a new kernel on a Red Hat-based system, the following command can be used:

sudo rpm -ivh kernel-{version}.{arch}.rpm

Replace {version} and {arch} with the appropriate version and architecture names for the kernel.

-

GRUB Configuration Update: When installing a new kernel, the GRUB configuration file will automatically be updated to include the new version. By default, the new kernel will be the default choice at boot, unless the system is reconfigured otherwise.

-

Coexistence of Kernels: By using the install option (-i), both the old and new kernels can coexist on the system. This allows for the flexibility to choose and boot into either kernel, providing the option to revert back to the old one if necessary.

-

Removing Older Kernels: It is not necessary to remove older kernel versions unless there is limited disk space. It is recommended to keep one or more older kernels available. However, if you wish to remove older kernel versions and other packages on Red Hat-based systems, the following command can be used:

sudo dnf remove --oldinstallonlyExercise caution when using this command, as it permanently removes older versions of the kernel and other packages.

Note: It is crucial to be careful when removing older kernel versions, as removing the wrong kernel can result in system instability or an inability to boot.

Using rpm2archive and rpm2cpio:

-

rpm2archive:

rpm2archiveis a utility used to convert RPM package files to tar archives. It creates a tar archive from an RPM package file. If “-” is provided as an argument, input and output are read from stdin and written to stdout. To convert an RPM package file to an archive, you can use the following command:rpm2archive bash-XXXX.rpmThis command will create a file named

bash-XXXX.rpm.tgz, which is the tar archive of the RPM package. -

Extracting with rpm2archive and tar: You can extract the contents of an RPM package in one step by using

rpm2archiveandtar. The command below reads the RPM package file (bash-XXXX.rpm) from stdin, converts it to an archive usingrpm2archive, and then extracts the files usingtar:cat bash-XXXX.rpm | rpm2archive - | tar -xvzThis command will extract the files from the RPM package to the current directory.

-

rpm2cpio:

rpm2cpiois another utility that can be used to convert RPM package files to cpio archives or extract files from the package file. To convert an RPM package file to a cpio archive, you can use the following command:rpm2cpio bash-XXXX.rpm > bash.cpioThis command creates a

bash.cpiofile, which is the cpio archive of the RPM package. -

Extracting files with rpm2cpio and cpio: You can extract one or more files from an RPM package using

rpm2cpioandcpio. Here are a few examples:rpm2cpio bash-XXXX.rpm | cpio -ivd bin/bash rpm2cpio logrotate-XXXX.rpm | cpio --extract --make-directoriesThe first command extracts the

bin/bashfile from the RPM package, while the second command extracts all files from thelogrotate-XXXX.rpmpackage and creates directories as necessary. -

Listing files in a package: To list the files contained in an RPM package, you can use the

rpmcommand itself. The following command lists the files in thebash-XXXX.rpmpackage:rpm -qilp bash-XXXX.rpmThis command displays the list of files included in the package, along with their paths.

Note: When using rpm2cpio, all files are extracted relative to the current directory.

Advantages of Using RPM

- Easy Package Management: RPM simplifies package management for system administrators. It allows them to easily determine the source package of a file, check the installed version, and ensure proper installation. Complete packages can be easily removed to free up disk space.

- Documentation Management: RPM distinguishes documentation files from the rest of the package, giving administrators the choice to install documentation on a system. This feature helps manage the documentation associated with software packages effectively.

- Code Modifications: RPM makes the job of software developers easier. When developers need to modify code to compile and execute correctly on a different operating system, RPM enables them to keep these changes separate from the original source code. This separation simplifies the process of incorporating new versions of the code and building versions of Linux for different architectures.

- Local and Remote Installation: RPM primarily installs packages from the local machine using absolute or relative paths. However, it also supports installation from remote locations using protocols like HTTP or FTP (deprecated).

- Package Versioning: RPM packages are versioned, allowing developers to release new versions of a program as separate packages. This versioning system helps ensure compatibility and provides a convenient way to manage updates and upgrades.

- Package Integrity: RPM uses checksums to ensure the integrity of packages during installation. This feature helps prevent corrupted or tampered packages from being installed on the system.

Note: The <distro> field in RPM package file names may actually represent the repository from which the package is obtained. It indicates that a given installation can utilize multiple package repositories, which are managed by higher-level package management tools like dnf, yum, or zypper.

dnf and yum

- The

dnfprogram provides a higher level of intelligent services for using the underlyingrpmprogram. It can automatically resolve dependencies when installing, updating and removing packages. It accesses external software repositories, synchronizing with them and retrieving and installing software as needed.

What is dnf?

-

dnfOverview:dnfis a package management tool that serves as a front end to RPM (Red Hat Package Manager). It is widely used by Linux distributions such as RHEL, CentOS, Fedora, and others.dnfoffers various features that make it valuable for package management tasks. -

Retrieving Packages: One of the notable features of

dnfis its ability to retrieve packages from one or more remote repositories. It acts as a package retrieval tool in addition to being an RPM front end. -

Dependency Resolution:

dnfexcels in resolving package dependencies. It can automatically determine and install the required dependencies for a package, simplifying the process of managing software dependencies. -

Repository Configuration: The configuration files for repositories in

dnfare stored in the/etc/yum.repos.ddirectory and have the extension.repo. These files define the repository details, including the repository name, description, base URL for package retrieval, and other settings. -

Sample Repository Configuration: A basic repository configuration file in

dnfmight have the following structure:[repo-name] name=Description of the repository baseurl=http://somesystem.com/path/to/repo enabled=1 gpgcheck=1The configuration specifies the repository name, its description, the base URL from where packages can be fetched, and other options like enabling repository checking using GPG keys.

-

Caching and Performance:

dnfcaches information and databases to enhance performance. To remove cached information, thednf cleancommand can be used with various options such aspackages,metadata,expire-cache,rpmdb,plugins, orall. This command allows cleaning specific cached data or removing all cached information. -

Enabling and Disabling Repositories:

dnfprovides flexibility in managing repositories. Theenabledoption in the repository configuration file can be changed to toggle the use of a particular repository on or off. Additionally, the-enablerepo somerepoand-disablerepo somerepooptions can be used with dnf commands to enable or disable specific repositories.

yum and dnf

yumtodnfTransition: During the transition from RHEL/CentOS 7 to 8,dnfreplaced yum as the default package manager. Fedora had been using yum for an even longer period. If you attempt to runyumcommands in some versions ofdnf, you may receive deprecation alerts that suggest using the appropriatednfcommand instead.- Backwards Compatibility:

dnfis designed to be backwards compatible, meaning that most common yum commands still work withdnf. This compatibility allows experienced yum users to gradually adapt todnfwhile continuing to perform day-to-day package management tasks. - Using

dnfas a Yum Replacement:dnfaccepts a subset of yum commands that cover the majority of common tasks. If you are familiar with yum, you can easily transition to usingdnfand achieve similar functionality. However, it is recommended to gradually learn and utilize the specificdnfcommands and options for better compatibility and future-proofing your package management workflows.

Note: The availability of specific yum commands in dnf may vary depending on the distribution, version, and configuration. It is advisable to consult the appropriate documentation or refer to the deprecation alerts provided by dnf to identify the recommended dnf command equivalents.

Queries

Here are some examples of queries and their corresponding commands:

#Searching for a package with a keyword:

dnf search keyword

#Displaying information about a package:

dnf info package-name

#Listing installed, available, or updates packages:

dnf list [installed | updates | available]

#Showing information about package groups:

dnf grouplist

#Showing information about a specific package group:

dnf groupinfo packagegroup

#Finding the owner of a package for a specific file:

dnf provides /path/to/file

#Install a package from a repository; also resolve and install dependencies:

sudo dnf install package

#Install a package from a local rpm file:

sudo dnf localinstall package-file

#Install a specific software group from a repository; also resolve and install dependencies for each package in the group:

sudo dnf groupinstall 'group-name'

#Remove a package from the system:

sudo dnf remove package

#Update a package from a repository (if no package is listed, update all packages):

sudo dnf update [package]

#Lists additional dnf plugins:

sudo dnf list "dnf-plugin*"

#Shows a list of enabled repositories:

sudo dnf repolist

#Provides an interactive shell in which to run multiple dnf commands (the second form executes the commands in file.txt):

sudo dnf shell

sudo dnf shell file.txt

#Downloads the packages for you (it stores them in the /var/cache/dnf directory):

sudo dnf install --downloadonly package

#Views the history of dnf commands on the system, and with the correction options, even undoes or redoes previous commands:

sudo dnf history

#Cleans up locally stored files and metadata under /var/cache/dnf. This saves space and does house cleaning of obsolete data:

sudo dnf clean [packages|metadata|expire-cache|rpmdb|plugins|all]