Storage

Computer storage is a hardware component that allows for the storage and retrieval of digital information. It is categorized into two main types:

- Primary storage (RAM, cache, ROM) for fast, temporary access to active data, and

- Secondary storage (hard drives, SSDs, cloud storage) for long-term, permanent data retention.

Storage Hardware and Architectures

Common Disk Types

There are a number of different hard disk types, each of which is characterized by the type of data bus they are attached to, and other factors such as speed, capacity, how well multiple drives work simultaneously, etc.

SATA (Serial Advanced Technology Attachment) : SATA disks were designed to replace the old IDE drives. They offer a smaller cable size (7 pins), native hot swapping, and faster and more efficient data transfer. They are seen as SCSI devices.

SCSI (Small Computer Systems Interface) : SCSI disks range from narrow (8 bit bus) to wide (16 bit bus), with a transfer rate from about 5 MB per second (narrow, standard SCSI) to about 160 MB per second (Ultra-Wide SCSI-3). SCSI has numerous versions such as Fast, Wide, and Ultra, Ultrawide.

SAS (Serial Attached SCSI) : SAS uses a newer point-to-point serial protocol, has a better performance than SATA disks and is better suited for servers. See the “SAS vs SATA: What’s the Difference” article by Zach Cabading to learn more.

USB (Universal Serial Bus) : These include flash drives and floppies. And are seen as SCSI devices.

SSD (Solid State Drives) : Modern SSD drives have come down in price, have no moving parts, use less power than drives with rotational media, and have faster transfer speeds. Internal SSDs are even installed with the same form factor and in the same enclosures as conventional drives. SSDs still cost a bit more, but price is decreasing. It is common to have both SSDs and rotational drives in the same machines, with frequently accessed and performance critical data transfers taking place on the SSDs.

IDE and EIDE (Integrated Drive Electronics, Enhanced IDE) : These are obsolete.

Disk Geometry

Rotational disks are composed of one or more platters and each platter is read by one or more heads. Heads read a circular track off a platter as the disk spins. Circular tracks are divided into data blocks called sectors.

Historically, disks were manufactured with sectors of 512 bytes; 4 KB is now most common by far; larger sector sizes can lead to faster transfer speeds. Linux still uses a logical sector size of 512 bytes for backward compatibility, but this is simply for pretend in software. A cylinder is a group which consists of the same track on all platters.

The physical structural image has become less and less relevant as internal electronics on the drive actually obscure much of it. Furthermore, SSDs have no moving parts or anything like the above ingredients, and for SSDs these geometry concepts make no sense.

we can see the geometry with fdisk:

sudo fdisk -l /dev/sdc |grep -i sector

Output:

Disk /dev/sdc: 1.8 TiB, 2000398934016 bytes, 3907029168 sectors

Units: sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

Sector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 4096 bytesExternal Storage Types - DAS, NAS and SAN

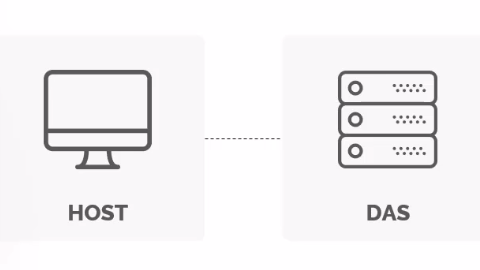

DAS (Direct Attached Storage)

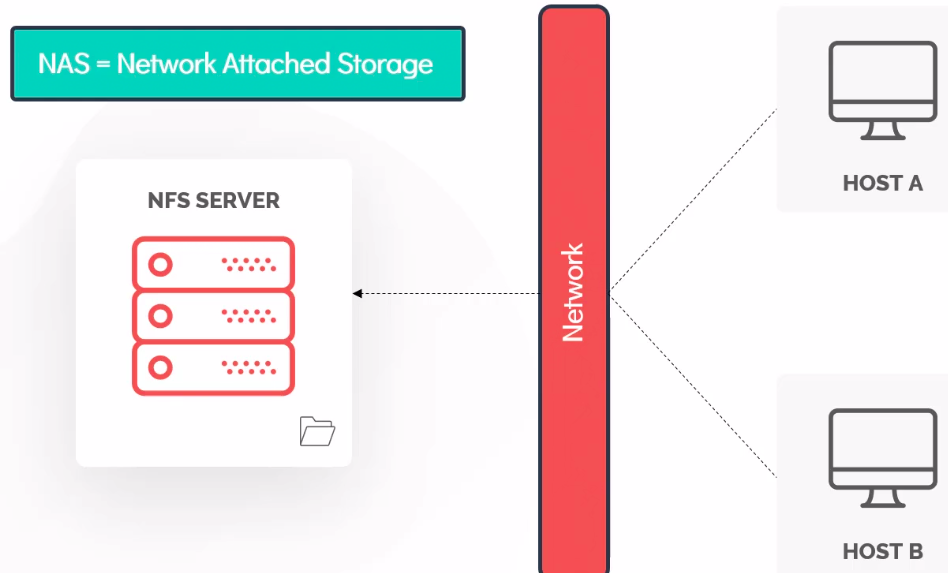

NAS (Network Attached Storage)

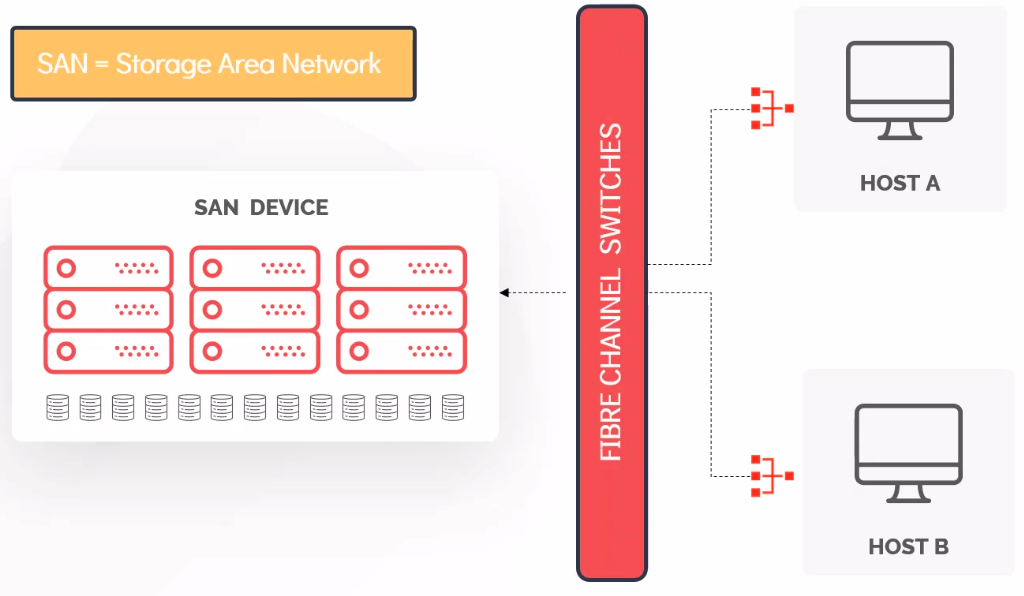

SAN (Storage Area Network)

| DAS | NAS | SAN |

|---|---|---|

| Block Storage | NFS/CIFS | FC or iSCsI |

| Fast and Reliable | Reasonably Fast and Reliable | Block Storage |

| Affordable | File Based Storage | Fast, Secure and Reliable |

| Dedicated to single host | Shared Storage | High Availability |

| ldeal tor small businesses | Not suitable for OS install | Expensive |

A Linux file system is a structured collection of files on a disk drive or a partition.

Disk Partitioning

What is a Partition?

-

A partition is a physically contiguous section of a disk, or what appears to be so in some advanced setups. It is a segment of memory and contains some specific data.

-

In machine, there can be various partitions of the memory. Generally, every partition contains a file system.

-

The general-purpose computer system needs to store data systematically so that we can easily access the files in less time. It stores the data on hard disks or some equivalent storage type. Reasons for maintaining the file system:

-

Primarily the computer saves data to the RAM storage; it may lose the data if it gets turned off. However, there is non-volatile RAM (Flash RAM and SSD) that is available to maintain the data after the power interruption.

-

Data storage is preferred on hard drives as compared to standard RAM as RAM costs more than disk space. The hard disks costs are dropping gradually comparatively the RAM.

The Linux file system contains the following sections:

- The root directory (

/) - A specific data storage format (EXT3, EXT4, BTRFS, XFS and so on)

- A partition or logical volume having a particular file system.

Why Partition?

There are multiple reasons as to why it makes sense to divide your system data into multiple partitions, including:

- Separation of user and application data from operating system files

- Sharing between operating systems and/or machines

- Security enhancement by imposing different quotas and permissions for different system parts

- Size concerns; keeping variable and volatile storage isolated from stable

- Performance enhancement of putting most frequently used data on faster storage media

- Swap space can be isolated from data and also used for hibernation storage.

The reasons to have distinct partitions include increased granularity of security, quota, settings or size restrictions. You could have distinct partitions to allow for data protection.

A common partition layout contains a /boot partition, a partition for the root filesystem /, a swap partition, and a partition for the /home directory tree.

Keep in mind that it is more difficult to resize a partition after the fact than during install/creation time. Plan accordingly.

Sizing Up Partitions

Most Linux systems should use a minimum of two partitions.

- root (

/) is used for the filesystem. Most installations will have more than one filesystem on more than one partition, which are joined together at mount points. It is difficult with most filesystem types to resize the root partition, but using LVM can make this easier. While it is certainly possible to run Linux with just the root partition, most systems use more partitions to allow for easier backups, more efficient use of disk drives, and better security. - Swap is used as an extension of physical memory. The usual recommendation is swap size should be equal to physical memory in size; sometimes twice that is recommended. However, the correct choice depends on the related issues of system use scenarios as well as hardware capabilities. Adding more and more swap will not necessarily help because at a certain point it becomes useless. One will need to either add more memory or re-evaluate the system setup.

On older rotational hard drive media, it may make more sense to have a separate swap partition, but on SSD-type media, this is unimportant. However, one still may want to put swap on slower and probably cheaper hardware. This is true whether you use a partition or a file, which is becoming a more prevalent choice.

Some distributions, including Ubuntu, default to use of a swap file rather than a partition:

- It is more flexible (resizing is easier, for example)

- It can be more dangerous, however, if error or bug spreads corruption

Types of Partitions

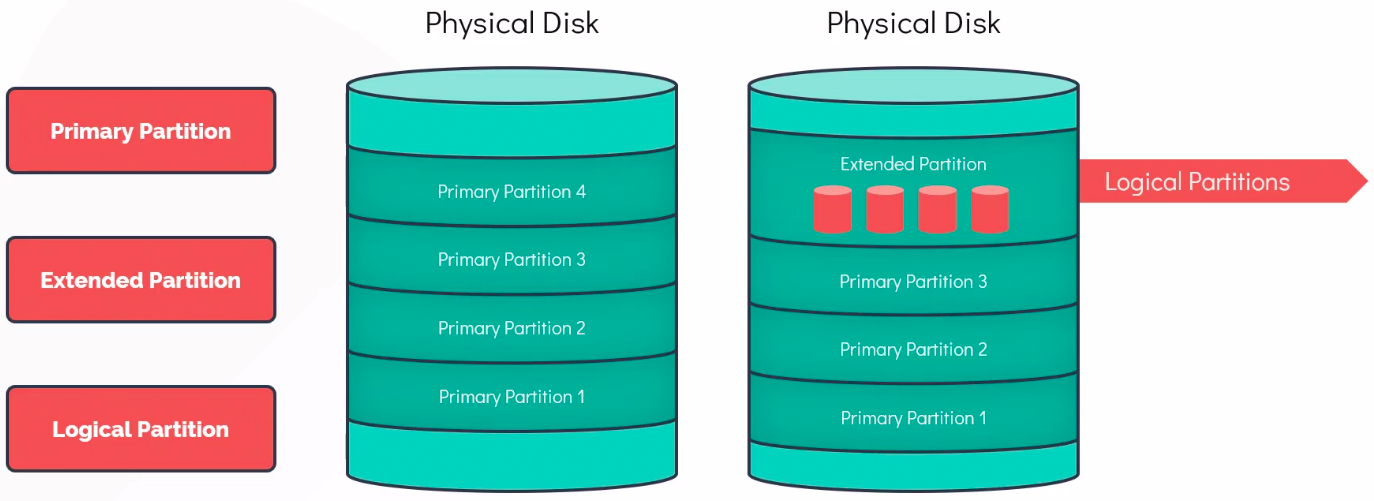

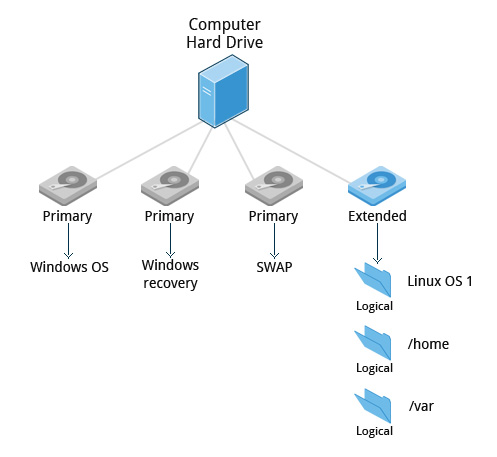

- Primary Partition: Type of partition which is used to boot an OS. Traditionally limited to 4 Primary Partitions per disk.

- Extended Partition: Cannot be used on its own and can host logical partitions in it. Its purpose is specifically to contain logical partitions. It acts as a container to overcome the four-primary-partition limit of the MBR scheme.

- Logical Partition: How a disk is partitioned is defined by partition table such as MBR (Master Boot Record), GPT (GUID partition table)

Partition Organization

Disks are divided into partitions. A partition is a physically contiguous region on the disk. On the most common architectures, there are two partitioning schemes in use:

- MBR (Master Boot Record)

- GPT (GUID Partition Table)

MBR dates back to the early days of MSDOS. When using MBR, a disk may have up to four primary partitions. One of the primary partitions can be designated as an extended partition, which can be subdivided further into logical partitions with 15 partitions possible.

When using the MBR scheme, if we have a SCSI, for example, /dev/sda, then /dev/sda1 is the first primary partition and /dev/sda2 is the second primary partition. If we created an extended partition /dev/sda3, it could be divided into logical partitions. All partitions greater than four are logical partitions (meaning contained within an extended partition). There can only be one extended partition, but it can be divided into numerous logical partitions.

GPT is on all modern systems and is based on UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface). By default, it may have up to 128 primary partitions. When using the GPT scheme, there is no need for extended partitions. Partitions can be up to 233 TB in size (with MBR, the limit is just 2TB).

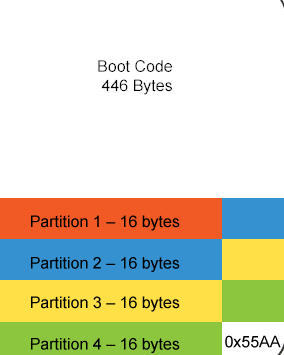

MBR Partition Table

The disk partition table is contained within the disk’s Master Boot Record (MBR), and is the 64 bytes following the 446 byte boot record. One partition on a disk may be marked active. When the system boots, that partition is where the MBR looks for items to load.

The structure of the MBR is defined by an operating system-independent convention.

- The first 446 bytes are reserved for the program code. They typically hold part of a boot loader program.

- The next 64 bytes provide space for a partition table of up to four entries. The operating system needs this table for handling the hard disk.

On Linux systems, the beginning and ending address in CHS is ignored.

Each entry in the partition table is 16 bytes long, and describes one of the four possible primary partitions. The information for each is:

- Active bit

- Beginning address in cylinder/head/sectors (CHS) format

- Partition type code, indicating: xfs, LVM, ntfs, ext4, swap, etc.

- Ending address in CHS

- Start sector, counting linearly from 0

- Number of sectors in partition.

Linux only uses the last two fields for addressing, using the linear block addressing (LBA) method.

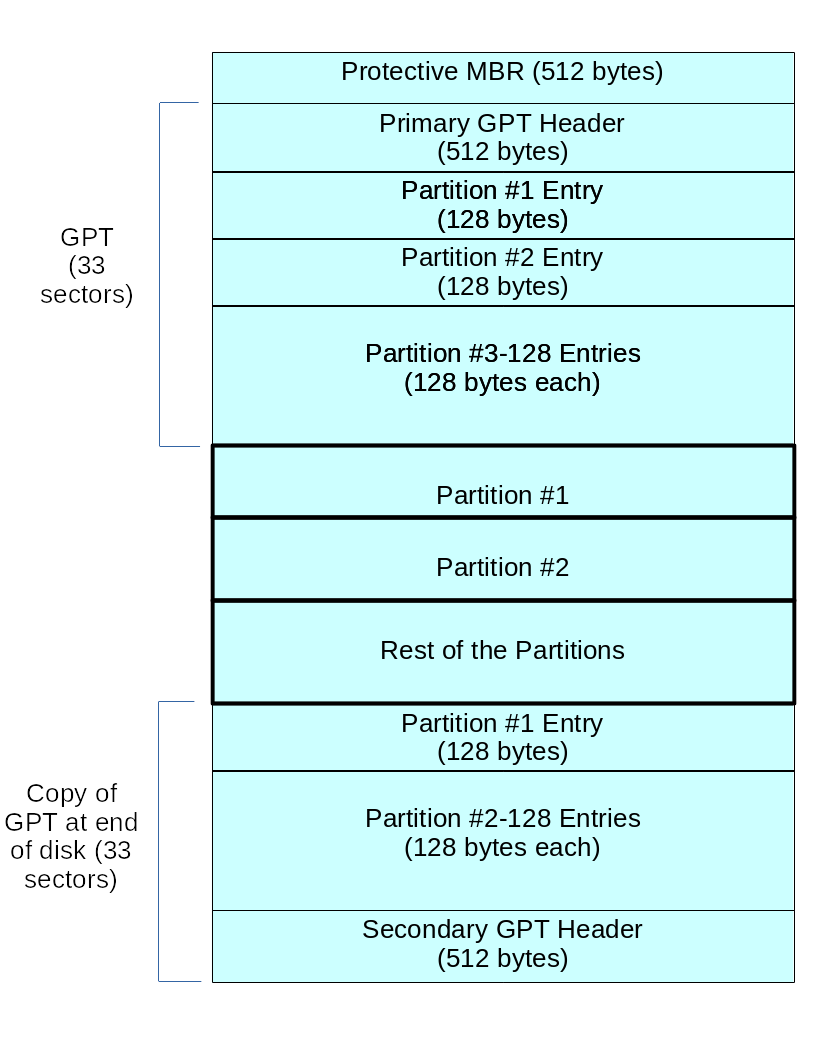

GPT Partition Table

Modern hardware comes with GPT support, MBR support will gradually fade away. The Protective MBR is for backwards compatibility, so UEFI systems can be booted the old way. There are two copies of the GPT header, at the beginning and at the end of the disk, describing metadata:

- List of usable blocks on disk

- Number of partitions

- Size of partition entries. Each partition entry has a minimum size of 128 bytes.

The blkid utility shows information about partitions.

#On a modern UEFI/GPT system run the following command:

sudo blkid /dev/sda8

Output:

/dev/sda8: LABEL="RHEL8" UUID="53ea9807-fd58-4433-9460-d03ec36f73a3" BLOCK_SIZE="4096" TYPE="ext4"

↪ PARTUUID="0c79e35b-e58b-4ce3-bd34-45651b01cf43"

#On a legacy MBR system use this command:

sudo blkid /dev/sdb2

Output:

/dev/sdb2: LABEL="RHEL8" UUID="6921b738-1e36-429a-89be-8b97cf2f0556" BLOCK_SIZE="4096" TYPE="ext4"

↪ PARTUUID="00022650-02"The GPT partition also gives a PARTUUID which describes the partition and stays the same even if the filesystem is reformatted. If the hardware supports it, it is possible to migrate an MBR system to GPT, but it is not hard to brick the machine while doing so. Thus, usually the benefits are not worth the risk.

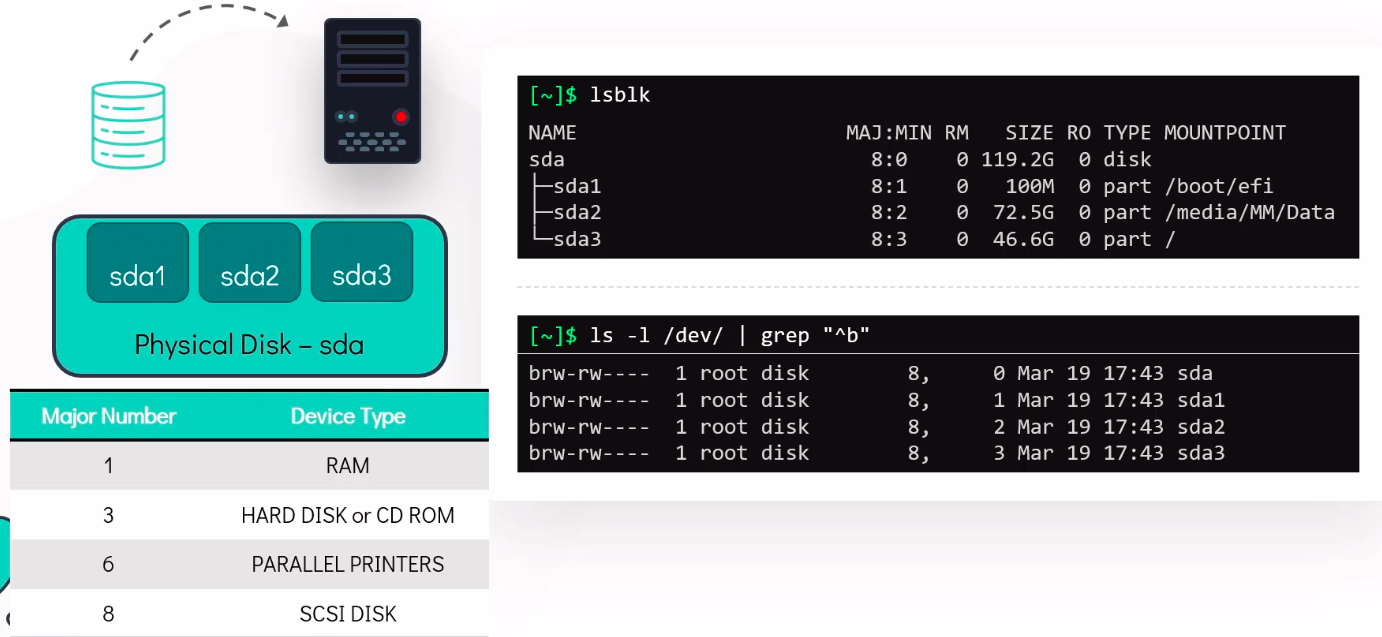

How Linux Identifies Storage

Block and Character Devices

When a program reads or writes data from a file, the requests go to a kernel driver. If the file is a regular file, the data is handled by a file_system driver and it is typically stored in zones on a disk or other storage media, and the data that is read from a file is what was previously written in that place. There are other file types for which different things happen.

When data is read or written to a device file, the request is handled by the driver for that device. Each device file has an associated number which identifies the driver to use. What the device does with the data is its own business.

-

Block devices (also called block special files) usually behave a lot like ordinary files

-

They are an array of bytes, and the value that is read at a given location is the value that was last written there.

-

Data from block device can be cached in memory and read back from cache; writes can be buffered.

-

Block devices are normally seekable (i.e. there is a notion of position inside the file which the application can change).

-

The name “block device” comes from the fact that the corresponding hardware typically reads and writes a whole block at a time (e.g. a sector on a hard disk).

-

Each block device has a Major and Minor number

- Major number is used to identify the type of the block device.

- The Minor number is used to distinguish individual physical or logical devices.

-

-

Character devices (also called character special files) behave like pipes, serial ports, etc.

- Writing or reading to them is an immediate action. What the driver does with the data is its own business.

- Writing a byte to a character device might cause it to be displayed on screen, output on a serial port, converted into a sound, Reading a byte from a device might cause the serial port to wait for input, might return a random byte (

/dev/urandom). - The name “character device” comes from the fact that each character is handled individually.

Naming Disk Devices and Device Nodes

The Linux kernel interacts at a low level with disks through device nodes normally found in the/dev` directory. Normally, device nodes are accessed only through the infrastructure of the kernel’s Virtual File System; raw access through the device nodes is an extremely efficient way to destroy a filesystem.

For an example of proper raw access, you can format a partition, as in this command:

sudo mkfs.ext4 /dev/sda9Device nodes for SCSI and SATA disks follow a simple xxy[z] naming convention, where

-

xxis the device type (usually sd), -

yis the letter for the drive number (a, b, c, etc.), and -

zis the partition number: -

The first hard disk is

/dev/sda -

The second hard disk is

/dev/sdb -

Etc.

Partitions are also easily enumerated, as in:

/dev/sdb1is the first partition on the second disk/dev/sdc4is the fourth partition on the third disk.

In the above, sd means SCSI or SATA disk.

Doing ls -l /dev will show you the current available disk device nodes.

blkid

blkid is a utility to locate block devices and report on their attributes. It works with the libblkid library. It can take as an argument a particular device or list of devices.

sudo blkid /dev/sda

/dev/sda: PTUUID="e7495134-61a2-473c-a31e-3c573a3d8e3e" PTTYPE="gpt"It can determine the type of content (e.g. filesystem, swap) a block device holds, and also attributes (tokens, NAME=value pairs) from the content metadata (e.g., LABEL or UUID fields).

blkid will only work on devices which contain data that is finger-printable: e.g., an empty partition will not generate a block-identifying UUID.

blkid has two main forms of operation:

- either searching for a device with a specific NAME=value pair, or

- displaying NAME=value pairs for one or more devices.

Without arguments, it will report on all devices.

lsblk

A related utility is lsblk which presents block device information in a tree format.

lsblk

NAME MAJ:MIN RM SIZE RO TYPE MOUNTPOINTS

sda 8:0 0 465.8G 0 disk

├─sda1 8:1 0 1G 0 part /boot/efi

├─sda2 8:2 0 1G 0 part /boot

└─sda3 8:3 0 463.8G 0 /home

zram0 251:0 0 8G 0 disk [SWAP]

nvme0n1 259:0 0 476.9G 0 disk

└─nvme0n1p1 259:1 0 476.9G 0 part /mnt/storageFile System

-

A file-system is a method of storing/finding files on a hard disk (usually in a partition).

-

One can think of a partition as a container in which a file-system resides, although in some circumstances, a file-system can span more than one partition if one uses symbolic links, which we will discuss much later.

-

Different types of file-systems supported by Linux:

- Conventional disk file-systems: ext3, ext4, XFS, Btrfs, JFS, NTFS, vfat, exfat, etc.

- Flash storage file-systems: ubifs, jffs2, yaffs, etc.

- Database file-systems

- Special purpose file-systems: procfs, sysfs, tmpfs, squashfs, debugfs, fuse, etc.

A comparison between file-systems in Windows and Linux:

| Windows | Linux | |

|---|---|---|

| Partition | Disk1 | /dev/sda1 |

| File-system Type | NTFS/VFAT | EXT3/EXT4/XFS/BTRFS… |

| Mounting Parameters | DriveLetter | MountPoint |

| Base Folder (where OS is stored) | C:/ | / |

Linux File System

Linux file system is generally a built-in layer of a Linux operating system used to handle the data management of the storage. It helps to arrange the file on the disk storage. It manages the file name, file size, creation date, and much more information about a file.

Virtual Filesystem (VFS)

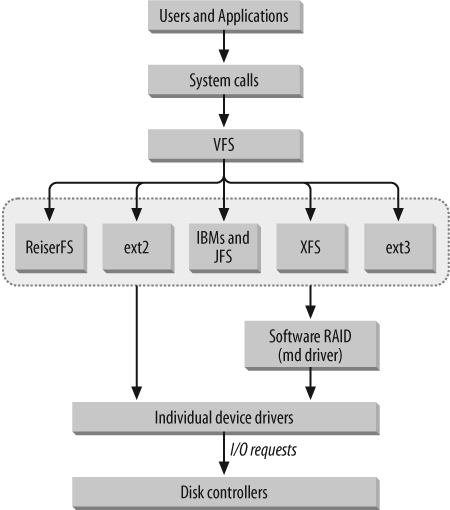

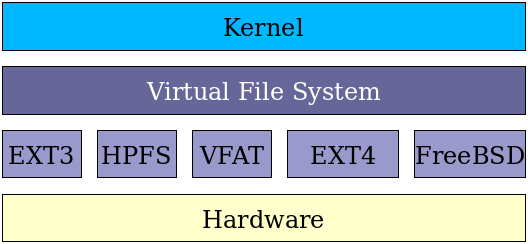

- Linux implements a Virtual File System (VFS), as do all modern operating systems.

- When an application needs to access a file, it interacts with the VFS abstraction layer, which then translates all the I/O system calls (reading, writing, etc.) into specific code relevant to the particular actual filesystem. Thus, neither the specific actual filesystem or physical media and hardware on which it resides need be considered by applications. Furthermore, network filesystems (such as NFS) can be handled transparently.

- This permits Linux to work with more filesystem varieties than any other operating system. This democratic attribute has been a large factor in its success.

- Most filesystems have full read and write access, while a few have only read access and perhaps experimental write access. Some filesystem types, especially non-UNIX based ones, may require more manipulation in order to be represented in the VFS.

- Variants such as

vfatdo not have distinct read/write/execute permissions for the owner/group/world fields; the VFS has to make an assumption about how to specify distinct permissions for the three types of user, and such behavior can be influenced by mounting operations. - There are non-kernel filesystem implementations, such as the read/write ntfs-3g, which are reliable but have weaker performance than in-kernel filesystems.

Extended FileSystem (ext3, ext4)

| Ext2 | Ext3 | Ext4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max File Size | 2 TB | 2 TB | 16 TB |

| Max Volume Size | 4 TB | 4 TB | 1 Exabyte |

| Supports Compression | Uses Journal | Uses Journal | |

| Supports Linux Permissions | Backward Compatible | Backward Compatible | |

| Long Crash Recovery | Uses Checksum for Journal |

- Journaling filesystems recover from system crashes or ungraceful shutdowns with little or no corruption, and do so very rapidly. While this comes at the price of having some more operations to do, additional enhancements can more than offset the price.

- In a journaling filesystem, operations are grouped into transactions. A transaction must be completed without error, atomically; otherwise, the filesystem is not changed. A log file is maintained of transactions. When an error occurs, usually only the last transaction needs to be examined. (ext3 | ext4 | reiserfs | JFS | XFS | btrfs)

Ext4 Filesystem features

-

The ext4 filesystem can support volumes up to 1 EB and file sizes up to 16 TB. Extents replace the older block mapping mechanism.

-

ext4is backwards compatible with ext3 and ext2. It can pre allocate disk space for a file. The allocated space is usually guaranteed and contiguous. It also uses a performance technique called allocate-on-flush (delays block allocation until it writes data to disk). ext4 breaks the 32,000 subdirectory limit of ext3. -

ext4uses checksums for the journal which improves reliability. This can also safely avoid a disk I/O wait during journalling, which results in a slight performance boost. -

Another feature is the use of improved timestamps. ext4 provides timestamps measured in nanoseconds.

ext4 Superblock and Block Groups

The superblock at the beginning contains information about the entire filesystem. It is followed by Block Groups composed of sets of contiguous blocks:

- Include administrative information

- High redundancy of information in block groups

- Other blocks store file data

The block size is specified when the filesystem is created. It may be 512, 1K, 2K, 4K, 8K, etc. bytes, but not larger than a page of memory (4kB on x86).

An ext4 filesystem is split into a set of block groups. The block allocator tries to keep each file’s blocks within the same block group to reduce seek times. The default block size is 4 KB, which would create a block group of 128 MB.

All fields in ext4 are written to disk in little-endian order, except the journal.

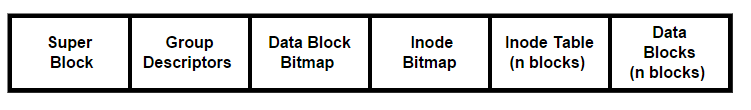

ext3 and ext4 Filesystem Layout

The layout of a standard block group is simple. For block group 0, the first 1024 bytes are unused (to allow for boot sectors, etc).

The superblock will start at the first block, except for block group 0. This is followed by the group descriptors and a number of GDT (Group Descriptor Table) blocks. These are followed by the data block bitmap, the inode bitmap, the inode table, and the data blocks.

Block Groups

The first and second blocks are the same in every block group, and comprise the Superblock and the Group Descriptors.

Under normal circumstances, only those in the first block group are used by the kernel; the duplicate copies are only referenced when the filesystem is being checked. If everything is OK, the kernel merely copies them over from the first block group.

If there is a problem with the master copies, it goes to the next and so on until a healthy one is found and the filesystem structure is rebuilt. This redundancy makes it very difficult to thoroughly fry an ext2/3/4 filesystem, as long as the filesystem checks are run periodically.

In the early incarnations of the ext filesystem family, each block group contained the group descriptors for every block group, as well as a copy of the superblock. As an optimization, however, today not all block groups have a copy of the superblock and group descriptors.

A Closer Look at the Superblock

Note that every time the disk is successfully mounted, the mount count is incremented. The filesystem is checked every maximum-mount-counts or every 180 days, whichever comes first.

Block size can be set through the mkfs command.

The superblock for the filesystem is stored in block 0 of the disk. This superblock contains information about the filesystem itself.

The Superblock contains global information about the filesystem

- Mount count and maximum mount count

- Block size for this filesystem

- Blocks per group

- Free block count

- Free Inode count

- OS ID

The Superblock is redundantly stored in several block groups.

Managing Ext4

Block and Inode Information for ext4: dumpe2fs

The block size is used to set the maximum number of:

- Blocks

- Inodes

- Superblocks

You can use the dumpe2fs program to get information about a particular partition. See dumpe2fs to scan the filesystem information such as limits, capabilities and flags, as well as other attributes.

sudo dumpe2fs /dev/sdb1

Output:

dumpe2fs 1.45.6 (20-Mar-2020)

Filesystem volume name: VMS

Last mounted on: /VMS

Filesystem UUID: fce521c7-e2ce-414a-8a7e-e2311640802f

Filesystem magic number: 0xEF53

Filesystem revision #: 1 (dynamic)

Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index filetype

needs_recovery extent 64bit flex_bg \

sparse_super large_file huge_file uninit_bg dir_nlink extra_isize

Filesystem flags: signed_directory_hash

Default mount options: user_xattr acl

Filesystem state: clean

Errors behavior: Continue

Filesystem OS type: Linuxxf .

Inode count: 14352384

Block count: 57388288

Reserved block count: 2869413

Free blocks: 22270800

Free inodes: 14352217

First block: 0

Block size: 4096

Block bitmap at 1056 (bg \#0 + 1056)

Inode bitmap at 1072 (bg \#0 + 1072)

Inode table at 1599-2110 (bg \#0 + 1599)

415 free blocks, 8192 free inodes, 0 directories, 8192 unused inodes

Free blocks: 33822-33985, 34550-34691, 38803-38911

Free inodes: 8193-16384

Group 2: (Blocks 65536-98303) csum 0xdde9 [INODE_UNINIT, ITABLE_ZEROED]

Block bitmap at 1057 (bg \#0 + 1057)

Inode bitmap at 1073 (bg \#0 + 1073)

Inode table at 2111-2622 (bg \#0 + 2111)

0 free blocks, 8192 free inodes, 0 directories, 8192 unused inodes

Free blocks:

Free inodes: 16385-24576

....Change Filesystem Parameters: tune2fs

tune2fs can be used to change filesystem parameters.

-

To change the maximum number of mounts between filesystem checks (max-mount-count) run this command:

sudo tune2fs -c 25 /dev/sda1 -

To change the time interval between checks (interval-between-checks) type the following command:

sudo tune2fs -i 10 /dev/sda1 -

To list the contents of the superblock, including the current values of parameters which can be changed use this command:

sudo tune2fs -l /dev/sda1 -

It basically shows the global information from dumpe2fs.

sudo tune2fs -l /dev/sdb1 tune2fs 1.45.6 (20-Mar-2020) Filesystem volume name: VMS Last mounted on: /VMS Filesystem UUID: fce521c7-e2ce-414a-8a7e-e2311640802f Filesystem magic number: 0xEF53 Filesystem revision #: 1 (dynamic) Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index filetype needs_recovery extent 64bit flex_bg sparse_super large_file huge_file uninit_bg dir_nlink extra_isize Filesystem flags: signed_directory_hash Default mount options: user_xattr acl Filesystem state: clean Errors behavior: Continue Filesystem OS type: Linux Inode count: 14352384 Block count: 57388288 Reserved block count: 2869413 Free blocks: 22270800 Free inodes: 14352217 First block: 0 Block size: 4096 Fragment size: 4096 ..... Filesystem created: Mon Mar 25 14:14:57 2025 Last mount time: Mon Sep 8 06:05:03 2025 Last write time: Mon Oct 8 06:05:03 2025 Mount count: 2003 Maximum mount count: -1 Last checked: Wed Oct 28 14:24:15 2025 Check interval: 0 (<none>) Lifetime writes: 14 TB ....

Working with EXT4

- Making a ext4 disk sdb2 at /dev/sdb2

mkfs.ext4 /dev/sdb2- Mounting file system

mkdir /mnt/ext4

mount /dev/sdb2 /mnt/ext4- Checking if file system is mounted

mount | grep /dev/sdb2

or

df -hP | grep /dev/sdb2- To make this mount available after reboot add entry to /etc/fstab

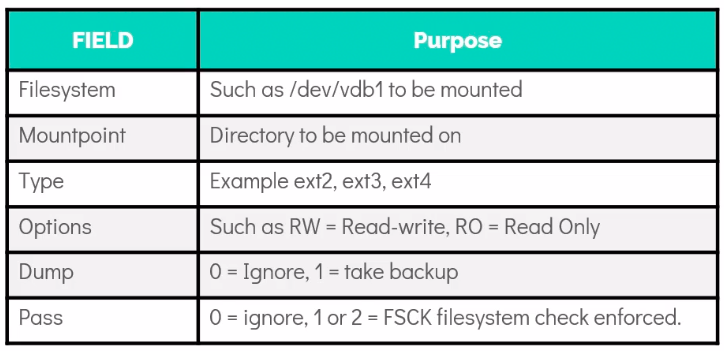

echo "/dev/sdb2 /mnt/ext4 ext4 rw 0 0" >> /etc/fstab/etc/fstab

Each record in the /etc/fstab file contains information about a filesystem to be mounted at boot, their standard mount points and what options should be used when mounting them. Each record in the file contains white space separated fields of information about a filesystem to be mounted:

- Device file name (such as

/dev/sda1), label, or UUID - Mount point for the filesystem (where in the tree structure is it to be inserted)

- Filesystem type

- A comma-separated list of options

- dump frequency used by the

dump -wcommand, or a zero which is ignored by dump fsckpass number or a zero - meaning do notfsckthis partition

The mount and umount utilities can use information in /etc/fstab.

Special & Network Filesystems

Special File Systems

- Linux widely employs the use of special filesystems for certain tasks. These are particularly useful for accessing various kernel data structures and tuning kernel behavior, or for implementing particular functions.

IMP

Some of these special filesystems have mount points, such as proc at /proc or sys at /sys and others do not.

Examples of special filesystems that have no mount point include sockfs or pipefs; this means user applications don’t interact with them, but the kernel uses them, taking advantage of VFS layers and code.

These special filesystems are really not true filesystems; they are kernel facilities or subsystems that find the filesystem structural abstraction to be a useful way to recognize data and functionality.

| FILESYSTEM | MOUNT POINT | PURPOSE |

| rootfs | None | During kernel load, provides an empty root directory |

| hugetlbfs | Anywhere | Provides extended page access (2 or 4 MB on X86) |

| bdev | None | Used for block devices |

| proc | /proc |

Pseudofilesystem access to many kernel structures and subsystems |

| sockfs | None | Used by BSD Sockets |

| tmpfs | Anywhere | RAM disk with swapping, re-sizing |

| shm | None | Used by System V IPC Shared Memory |

| pipefs | None | Used for pipes |

| binfmt_misc | Anywhere | Used by various executable formats |

| devpts | /dev/pts |

Used by Unix98 pseudo-terminals |

| usbfs | /proc/bus/usb |

Used by USB sub-system for dynamical devices |

| sysfs | /sys |

Used as a device tree |

| debugfs | /sys/kernel/debug |

Used for simple debugging file access |

NFS (Network File System)

- Does not store data in blocks instead it saves it in form of files.

- Works on Server-client model.

- Directory sharing in NFS is known as Exporting.

- NFS server maintains an export configuration file at

/etc/exportsthat define the clients which should be able to access the directories on the server. - Once export conf is updated the directory is shared to the clients by using the

export-fscommand. It is used to apply the changes without restarting the NFS service.

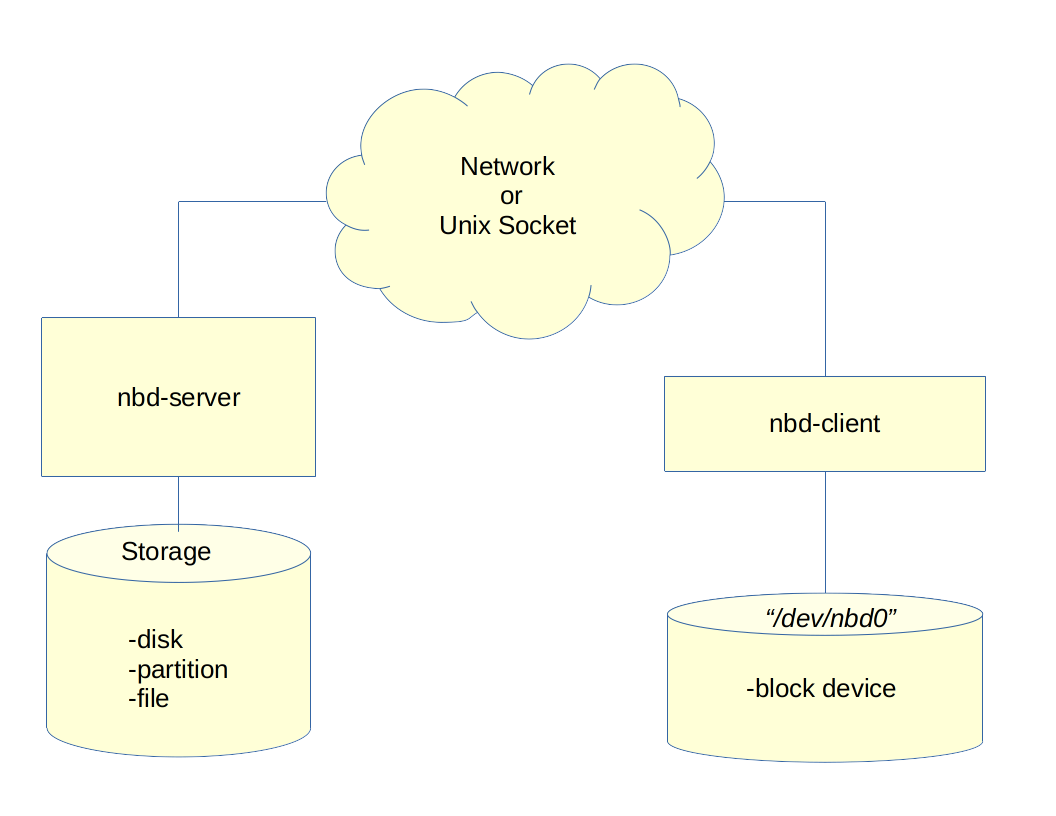

Network Block Device (NBD)

A Network Block Device is a Linux protocol designed to export a block device from a source computer (server) to a target (client). The NBD can use either Unix sockets or TCP/IP for communication.

The unit that is exported by the server can be one or more files, image, or a block device. On the client side, the data blob presented by the server is mapped through an nbd kernel module and accessed as a block device. The client side block devices can be recognized by names like /dev/nbd0, /dev/nbd1, etc.

In its simplest configuration the datastream is not encrypted. However, encryption is available and part of the NBD specification.

Some additional information and reference documents can be found at the following locations:

To configure an nbd client/server pair, the general steps are:

- Define something to export on the server

- Define the item to be shared to the server

- Connect the client

- The device can be partitioned and formatted like any other block device by using the

/dev/nbd0,/dev/nbd1devices - Almost any filesystem type can be used with the nbd devices once partitioned

The steps I have used are:

- Use

ddto create an empty file - Define the item to be shared by the server in a configuration file

- Activate the nbd kernel module

- Query the server with the client using the export name, IP address and port

- Associate the local

/dev/nbdblock driver with the server with thenbd-clientcommand - Use

fdiskto partition the nbd - Add a filesystem to the nbd and mount it

NBD User Utilities

There are several nbd clients and server packages available, including:

nbdkit: CentOS, Fedora, Debian, Ubuntunbd-clientandnbd-server: Ubuntu, Debiannbd(from GitHub): CentOS, Fedora, Debian, UbuntuxNBD-clientandxNBD-server: Debianqemu-img: CentOS

In general the clients and servers can be mixed and matched, so careful testing in your use case is recommended.

An example of the user and administrator utilities for Ubuntu 22.04:

- nbd-server-conf is an example of a configuration file for the server containing:

- IP address and port to listen for connections

- storage device to export as a disk

- some optional control elements

- nbd-server is the server side component to answer connection requests and communication

- nbd-server man page contains the specifics for server configuration. This information may vary between distributions.

- nbd-client is used to query the server and make the connection to the server

- nbd-client man page contains client-related information to make the connection to the server.

These utilities may have different names and include different functions depending on how they are packaged by the distributions.

Network Block Device Example

Some example commands for the clients and server are:

-

The server was CentOS-8-Stream using the nbd package from GitHub.

-

The client was CentOS-8-Stream using the nbd package from GitHub.

-

Ensure the nbd kernel modules are loaded using the following command:

sudo modprobe -i nbd- Connect the exported foo on 192.168.242.160 to the local device /dev/nbd10:

sudo nbd-client -N foo 192.168.242.160 /dev/nbd10Examples of some commands from an Ubuntu installation:

- Start the nbd server process with the following command:

sudo nbd-server -C nbd-server.conf- List the exports on the server from the client with the following command:

sudo nbd-client -l 127.0.0.1 10042- Connect the export foo to the local device /dev/nbd0:

sudo nbd-client -N foo 127.0.0.1 10042 /dev/nbd0